Java Licensing Explained

What is Oracle Java?

Oracle Java Licensing and the product is a version of the Java programming language and software platform developed and maintained by Oracle Corporation. Java is a popular programming language that is used to develop a wide range of applications, including web, mobile, and desktop applications. Oracle Java is specifically designed to be used in enterprise environments, and it includes a number of features and tools that are optimized for use in business settings.

Java is known for being a platform-independent programming language, meaning that programs written in Java can run on any device that has a Java Virtual Machine (JVM) installed, regardless of the underlying hardware and operating system. Oracle Java includes the Java Development Kit (JDK), which is a set of tools that developers can use to create Java programs, and the Java Runtime Environment (JRE), which is a software platform that allows Java programs to run on a device.

Oracle Java is a commercial product, and it is typically used in enterprise environments where developers need access to advanced features and support from Oracle. It is also used in other settings where the performance and stability of the Java platform is a critical factor.

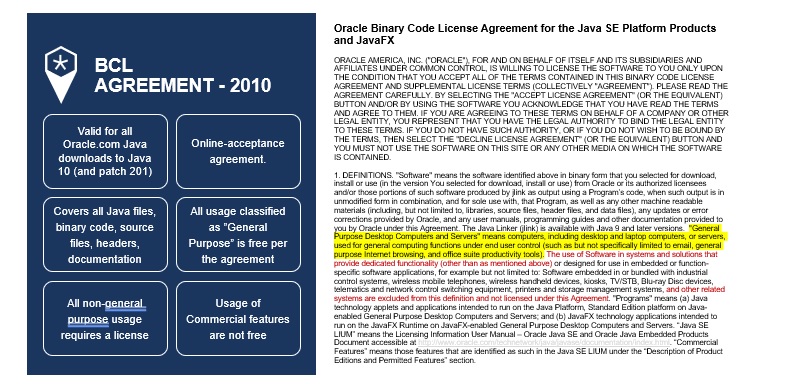

What is Oracle Binary License Agreement ?

The Oracle Binary Code License Agreement (BCLA) is a legal agreement between Oracle Corporation and the user of Oracle software products. The BCLA outlines the terms and conditions under which Oracle software products can be used, including the rights and responsibilities of the user and Oracle.

The BCLA applies to all Oracle software products that are distributed in binary form, including the Oracle Database, Oracle Java, and Oracle Linux. It defines the terms under which users can use the software, including the scope of use, distribution, and modification of the software.

The BCLA also outlines the terms of support and maintenance for Oracle software products, including the types of support that are available and the terms under which Oracle will provide updates and fixes to the software.

It is important to carefully read and understand the terms of the BCLA before using Oracle software products, as it specifies the legal rights and responsibilities of both the user and Oracle. By using Oracle software, the user is accepting the terms and conditions outlined in the BCLA.

Explain Java Licensing changes in 2019

In 2019, Oracle made changes to its licensing model for Java Standard Edition (Java SE), the version of Java that is used for developing general-purpose applications. Prior to these changes, Oracle offered two main options for licensing Java SE:

- Oracle Java Development Kit (JDK) with a Binary Code License Agreement (BCLA): This option was available to users who wanted to use Oracle Java for development purposes. It included the JDK, a set of tools for developing Java applications, and was licensed under the BCLA.

- Oracle Java Runtime Environment (JRE) with a Binary Code License Agreement (BCLA): This option was available to users who wanted to run Java applications on their devices. It included the JRE, a software platform that allows Java programs to run, and was licensed under the BCLA.

What is Java SE commercial features?

Java SE commercial features are additional features and tools that are included in the Oracle Java Standard Edition (Java SE) commercial release, but are not included in the open-source version of Java SE. These features are intended for use in enterprise environments and are available to users who have purchased a license to use Oracle Java SE.

Some examples of Java SE commercial features include:

- Advanced Management Console: This tool provides a web-based interface for managing and monitoring Java SE deployments, including the ability to monitor Java SE applications and manage Java SE licenses.

- Flight Recorder: This tool allows developers to collect and analyze detailed performance data from Java SE applications in real-time.

- Java Mission Control: This tool provides advanced tools for analyzing and troubleshooting Java SE applications, including the ability to monitor and manage Java SE applications in real-time.

- Oracle Java SE Support: Oracle provides support for Java SE commercial users, including access to updates and fixes, technical support, and training resources.

Overall, Java SE commercial features are intended to provide users with advanced tools and support for developing and managing Java SE applications in enterprise environments.

How much does Oracle Java cost ?

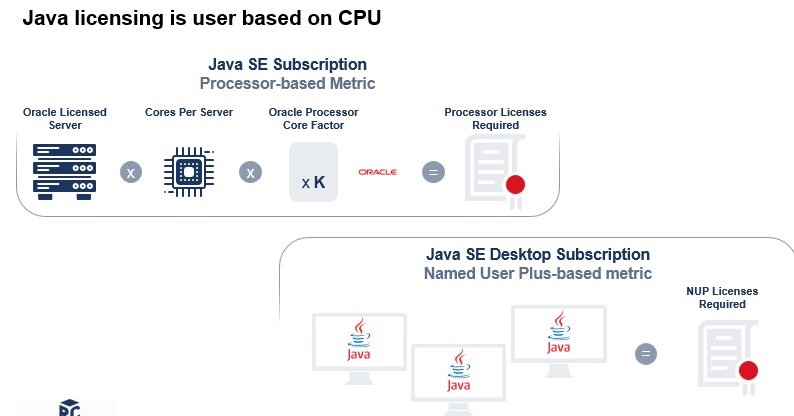

The cost of Oracle Java depends on the version of Java that you are using and the type of license that you choose. Oracle offers several different versions of Java, including the Java Standard Edition (Java SE) and the Java Enterprise Edition (Java EE).

For Java EE, Oracle offers several different licensing options, including:

- Oracle Java SE Subscription – this is the server edition and need to apply licensing rules and policies including VMware.

- Oracle SE Desktop Subscription – this is a license per user not per server.

Overall, the cost of Oracle Java can vary significantly depending on the version of Java that you are using and the type of license that you choose

Is Java free ?

Java is a programming language and software platform developed by Oracle Corporation. The core Java technology is available as an open-source software under the GNU General Public License (GPL), which means that it is free to use, distribute, and modify.

However, Oracle also offers a commercial version of Java called the Oracle Java Standard Edition (Java SE), which includes a number of additional features and tools that are not available in the open-source version. Oracle Java SE is not free and requires a license to use.

If you want to use the open-source version of Java, you can download it from the OpenJDK website (https://openjdk.java.net/) and use it without paying any fees. However, if you want to use the commercial version of Java SE or access advanced features and support from Oracle, you will need to purchase a license.

It is important to note that while the open-source version of Java is free to use, it may not include all of the features and tools that are available in the commercial version of Java SE. If you need access to these features, you may need to purchase a license for Oracle Java SE.

Does any Oracle products include a java license ?

Some Oracle products may include a license for Oracle Java Standard Edition (Java SE), a version of the Java programming language and software platform developed and maintained by Oracle Corporation. Oracle Java SE includes a number of features and tools that are optimized for use in enterprise environments, and it is used to develop a wide range of applications, including web, mobile, and desktop applications.

Examples of Oracle products that may include a license for Oracle Java SE include:

- Oracle Database: Oracle’s flagship database product includes a license for Oracle Java SE, which can be used to develop Java applications that run on the Oracle Database.

- Oracle Fusion Middleware: This product includes a license for Oracle Java SE, which can be used to develop Java-based applications that are built on top of Oracle Fusion Middleware.

- Oracle Cloud: Oracle’s cloud computing platform includes a license for Oracle Java SE, which can be used to develop Java applications that run on Oracle Cloud.

It is important to note that the specific licensing terms for Oracle Java SE may vary depending on the product and the version of Java SE that is included. It is recommended that you review the terms of the license for Oracle Java SE carefully to understand the specific rights and responsibilities that are associated with using the software. If you have any questions about the licensing for Oracle Java SE

Is Oracle auditing customers for Java ?

Oracle may audit customers who are using Oracle Java Standard Edition (Java SE) to ensure compliance with the terms of the license agreement. Oracle may conduct audits to verify that customers are using Oracle Java SE in accordance with the terms of the license, including the number of users and devices on which the software is installed, and the specific features and tools that are being used.

Oracle may conduct audits through various methods, including on-site visits, online reviews, and other methods. Customers who are being audited may be required to provide documentation and other information to Oracle to support the audit.

If Oracle determines that a customer is not in compliance with the terms of the Oracle Java SE license, the customer may be required to pay additional fees or take other actions to bring their usage of the software into compliance.

Is Java still free for commercial use ?

The core Java technology is available as an open-source software under the GNU General Public License (GPL), which means that it is free to use, distribute, and modify. This includes the use of Java for commercial purposes.

However, Oracle also offers a commercial version of Java called the Oracle Java Standard Edition (Java SE), which includes a number of additional features and tools that are not available in the open-source version. Oracle Java SE is not free and requires a license to use.

If you want to use the open-source version of Java for commercial purposes, you can download it from the OpenJDK website (https://openjdk.java.net/) and use it without paying any fees. However, if you want to use the commercial version of Java SE or access advanced features and support from Oracle, you will need to purchase a license.

Oracle Java licensing changes

Oracle has made several changes to the licensing model for its Java Standard Edition (Java SE) software over the years. Some of the notable changes include:

- Introduction of the Oracle Java SE Subscription: In 2019, Oracle introduced the Oracle Java SE Subscription, which provided users with access to Oracle Java SE and support from Oracle for a fixed annual fee. This was intended to make it easier for users to access Oracle Java SE and get support from Oracle.

- Introduced a new license agreement, Java OTN SE which made all commercial use licensable.

Overall, these changes were intended to make it easier for developers and users to access Oracle Java SE and to provide more flexible and user-friendly licensing options.

If you need help with Oracle Java Licensing – contact our team to help you conduct a Java license review and avoid the Java license audit.